Drug policy as an integral part of state health policy - international examples

-

Copyright

© 2017 PRO MEDICINA Foundation, Published by PRO MEDICINA Foundation

User License

The journal provides published content under the terms of the Creative Commons 4.0 Attribution-International Non-Commercial Use (CC BY-NC 4.0) license.

Authors

Medicines policy plays a major role in protecting, maintaining and restoring people’s health and is an integral part of state health policy. It embraces brand and generic drugs, biologics, vaccines and natural health products. Drug policy ensures an access to safe and effective medicines while reducing patient participation in treatment costs. Medicine policy includes among others, patent law, licensing, prescribing, pricing, reimbursement, formulary management, eligibility, pharmacy, funding of research in the life sciences services[1]

The national pharmaceuticals policy is the one based on drug use where patients receive medications according to their clinical needs, in the individual required doses, in the right time, at the lowest possible cost [3].

In this article national medicine policies in Australia, United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, South Africa and Poland were presented from the viewpoints of drugs’ spending, regulations and practice.

The general policy framework addresses the inherent tensions within the objectives of attaining affordable access to medicines, while maintaining a viable pharmaceutical industry, and achieving quality medicines and healthcare systems.

In Poland development of medicine policy is under creation.

Introduction

Medicines policy plays a major role in protecting, maintaining and restoring people’s health. The regular provision of appropriate medicines of assured quality, in adequate quantities and at reasonable prices, is therefore a concern for all national governments[1]’[2].

Drug policy is an integral part of state Health Policy. It is also prevention and conducting health education for specialists and patients. Drug policy ensures an access to safe and effective medicines while reducing patient participation in treatment costs. Pharmaceutical policy is a branch of health policy that deals with the development, provision and use of medications within a health care system. It embraces drugs (both brand name and generic), biologics (products derived from living sources, as opposed to chemical compositions), vaccines and natural health products.

Medicine policy includes:

-

Funding of Research in the Life Sciences

-

Patent Law

-

Licensing

-

Pricing

-

Reimbursement

-

Formulary management

-

Eligibility

-

Prescribing

-

Pharmacy services[3]

A national pharmaceuticals policy is one that aims at ensuring that people get good quality drugs at the lowest possible price, and the drugs are prescribed in order to treat the patient's illness at minimum as is required. A demanded drug policy is one based on drug use in which patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in the individual requirements doses, for a specified time keeping the lowest cost to them and their community[3]. Total global spending on medicines will exceed one trillion U.S. dollars (Tn) for the first time in 2014 and reach almost $1.2 trillion in 2017 [3,12]. Many countries are moving toward Universal Health Coverage, ensuring access to medicines and other elements of healthcare for all. Regarding health care development it is important to understand how the market for pharmaceuticals performed, what kind of molecules, brands and generics are registered, what is the demand for use of madicines in retail pharmacies and in hospitals. Pharmaceutical companies make their income by selling drugs under their trade names, promoting them to pharmacists and to doctors. Doctors often prescribe branded drugs, which are more expensive than generic drugs which have the same efficacy.[4]

National medicines policy requires regulations providing access to medicines while avoiding the polypragmasy.While overuse and misuse of medicines are common in many countries, the poor availability of essential medicines is a major problem in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) and for the poorer segments of the population [3]. The population ageing, emergence of new diseases, increasing antimicrobial resistance, increasing use of preventive medicines, and the availability of new and expensive medicines displaying little or no therapeutic benefit over existing treatments have incremental impact on increasing spending on medicines [4,5]. In addition to high expenditures, a huge impact on improved medicine access have factors such as changing patterns of morbidity and the increasing role of the pharmaceutical sector in delivering medicines [6,7]. These factors of medicine access are specific to each country and relate to the national political situation, as well as the economic situation and existing legislation. These access problems have persisted despite efforts by governments, development agencies and the World Health Organization (WHO) to improve access to essential medicines, to promote rational use and to ensure that quality assured medicines are used.

The main causes of irrational drug use are the following:

• Irrational prescribing practices of doctors

• Dispensing by pharmacists and drug sellers

• Drug pricing policies and promotional activities of the pharmaceutical industry

• Insufficient information, education and communication on rational drug use to providers and consumers

• Insufficient effective control and regulatory mechanisms on drug use

• Insufficient political will and leadership to promote rational use

The stakeholders play an important role and have an impact on universal access and a rational use of medicines. Thus, there is a general need to develop the medicine policies based on universal principles, but at the same time adapted to the national situation in a given country, to meet health needs of its inhabitants. A national medicine policy provides a comprehensive framework for the development of all components of the national pharmaceutical sector due to health care strategy development monitoring and periodic reviews, which are essential [9].

Innovation, the ultimate engine of growth for the global provision of medicines, experiences revival of activity through 2017, with an increased number of global innovative launches since 2010. More specialty medicines will be launched, including an increasing number of very small patient population orphan drugs. Unfortunately they are still many unmet needs in many serious diseases treated in the specialist sector, for example in oncology. Current innovative launches are yielding significant transformations in some disease areas, including advances in the treatment of melanoma or hepatitis C. In countries, such as South Africa and Laos, where access to regular cancer screening and treatment may be limited or unavailable, the goverment have recently adopted extensive and influential vaccination programs for girls to prevent cervical cancer. There is still a lot of work to be done. The progress is being made, but the right combination of incentive and spend still needs to be pursued in order for medicines to play their full potential role in improving healthcare globally.

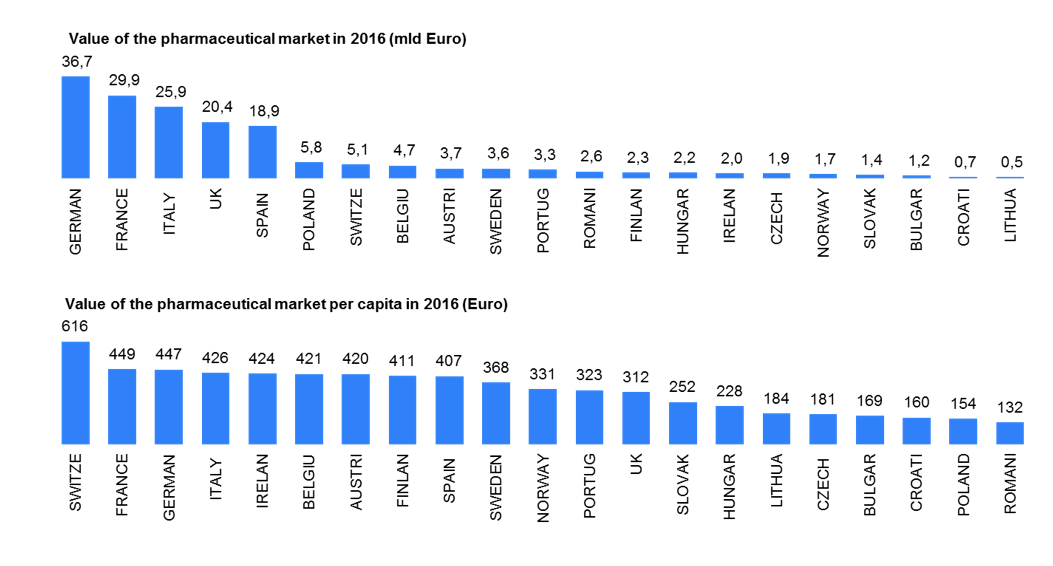

Source: IMS Midas 12/2016 | Retail&Hospital market(ATC1 A-V) | Ex-factory price | Euro | Eurostat 2016

Spending levels on medicines for specific disease areas (rare disease) and medicine spending per capita together with growth rates are starkly different between mature and pharmerging markets in 2017. Increasing share of all medicines including biologics, biosimilars and non-original biologics will requires more investment in new molecules and therapies. IMS Market Prognosis publication forecasts total global spending on medicines will reach about $1.2Tn in 2017, an increase of $205-235Bn from 2012[11]

Methods

In this article the authors are compering the international experience in creating and developing model of medicines policy to analysis of difference and common features. The authors chose the models of national medicine policies in Australia, United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, South Africa and Poland to presented from the viewpoints of drugs’ spending, regulations and practice.

The authors wish to purposely collate the key elements of the medicines policies from the countries whose health care systems vary substantially in terms of:

· overall affluence of the country’s health care system

· developing vs developed economies

· new vs incumbent legislation

· moderately vs highly regulated health care systems

· closed vs adaptable

· mechanisms to curtail reimbursement spending

· dealing with generics and preferences for local manufacturers

The review will both lead to discovering the elements of the medicines policy that may not be considered crucial in Poland at the moment, but are an important part of the systems in other countries as well as to giving tips on how the crucial elements for Poland are organized elsewhere.

Results

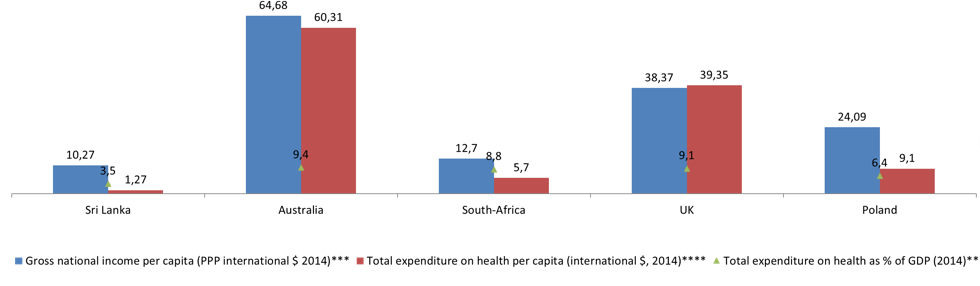

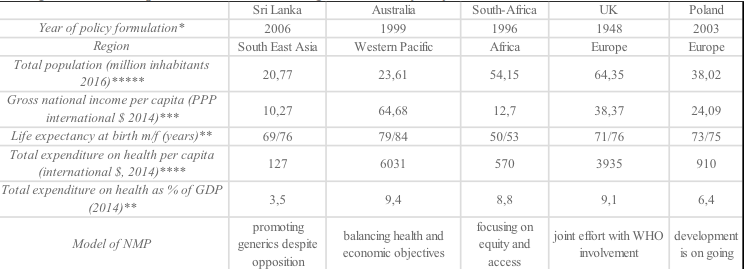

Source:https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/february201

GDP gross domestic product, PPP Purchasing Power Parity, m/f male/female.

Source:

* http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.ishrworld.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/GNIPC_2014.pdf

** http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS

*** https://pl.tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gdp-per-capita

**** http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP

The general policy framework addresses the inherent tensions within the objectives of attaining affordable access to medicines, while maintaining a viable pharmaceutical industry, and achieving quality medicines and healthcare systems.

Australia’s national medicines policy – balancing health and economic objectives

To reach the goal, the policy framework addresses the inherent tensions of often contradictory objectives of attaining affordable access to medicines, while maintaining a viable pharmaceutical industry, and achieving quality medicines and healthcare systems [14].

In Australia, the National Medicines Policy (NMP) have been in place since 1999 and is a well-established framework based on partnerships between Governments – Commonwealth, States and Territories – health educators, health practitioners, and other healthcare providers and suppliers, the medicines industry, healthcare consumers, and the media. All of them cooperate to develop and promote the objectives of the policy. The term ‘medicine’ includes prescription and non-prescription medicines as well ascomplementary healthcare products. The National Medicines Policy has focus on elements of social and economic policy. To achieve objectives of the policy it is required from each elements drawing on their unique perspectives and partner's abilities, which focuses first of all on patient’s needs. [24]

In Australia, there are a few aspects in access to medicines, such as risks of overuse of medicines and therefore potential public health implications. Both are addressed through scheduling or controls, which requires the intervention by suitably qualified health practitioners to ensure appropriate use.

Regarding cost of medicines and patient treatment, Australia’s Government consider people should not have a substantial barrier to medicines access. Therefore the increasing affordability of important medicines is required. An existence of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) facilitates access to certain product group by subsidising costs. Moreover the subsidies occur when hospitals supply medicines to patients, which are not costless, but the community as a whole must bear them.[25]

All of the market access mechanism increase community consciousness on how high the costs of medicine treatment are, that's why both the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the treatments need to be considered in making decisions about subsidisation. The Australian policy’s four major objectives are to ensure:

1. timely access to the needed medicines through the Therapeutic Goods Administration and through the Pharmaceutical and Repatriation Benefits Schemes

2. appropriate use of medicines

3. that medicines meet appropriate standards of quality, safety and efficacy

4. maintaining a responsible and a viable national pharmaceutical industry [24]

The overall goal of Australia’s NMP is ‘to meet medication and related health service needs, so that both optimal health outcomes and economic objectives are achieved’[25]. To reach this goal, the framework of medicine policy is addressed to affordable access to medicines (while maintaining a viable pharmaceutical industry), and keep achieving high treatment efficiency and therefore good quality of health systems.[26]

Sri Lanka’s national medicines policy – promoting generics despite opposition

‘Generic promotion and substitution are two components in the NMP that the industry vehemently opposed and they have successfully lobbied to delay the implementation of the NMP’[12].

The two first health reforms attempting at a National Medicine Policy (NMP) development (in 1991 and 1996) have failed because of the absence of participation of civil society. Currently development of NMP in Sri Lanka have been facilitated thanks to the number of national seminars, meetings and workshops focused on all stakeholders' needs. All imports and production of pharmaceuticals are going to be limited to the approved drugs listed in the national formulary due to and under an integrated national pharmaceutical policy. The public and private health sectors must obtain all their requirements from the central buying agency. The central buying agency is calling for worldwide bulk tenders which are limited to the approved drugs listed. All medical personnel must be informed about drugs and therapeutics effects. It is essential to delivery the promotional materials on them. The cost of promotion materials are increasing the costs of supplied drugs. The objectives of the Sri Lankan National Medicinal Drug Policy are:

1. Sustainable and equitable delivery of the good quality and safe medicines relevant to the health care needs

2. The rational use of medicines by healthcare professionals and consumers

3. The strong emphasis on the promotion of local essential medicines manufacturers

The Sri Lankan National Medicinal Drug Policy (NMDP) is focused on developing the Essential Medicines Concept. All medicines policy should be based on the health sector, but coordinate with relevant areas such as education, finance, agriculture, animal husbandry, pharmaceutical industry and trade.

The Sri Lankan NMDP will have the following elements:

1. Selection of essential medicines

2. Affordability and Equitable Access

3. Financing options

4. Supply systems and donations

5. Regulation and quality assurance

6. Quality Use of Medicines

7. Research

8. Human resources

9. Viable Local Pharmaceutical Industry

10. Monitoring and evaluation [13]

In Sri Lanka, which has become the model of national pharmaceutical policy, drug information was provided from official sources. All medicines prescriptions (edited by the National Formulary Committee NFC – established by the Ministry of Health), were quarterly published by the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation (SPC) and distributed to all medical personnel. Inappropriate promotional drug practices were removed to avoid the overuse and inherent costs. The Sri Lankan policy was supported by the WHO and other United Nations agencies with enormous benefit to the third World countries. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat examined the Sri Lankan experience, concluding that an analysis of the Sri Lankan model could give other developing countries an insight into ways of formulating, developing and implementing integrated national pharmaceutical policies[13].

South Africa’s national medicines policy

In South Africa the whole health care system is focused on highly effective medicines and equity for all population: white and black.

The focus of South Africa’s first single NMP was on equity. The health care system was generous and highly effective, but only for the white population. Two separate drafts of national medicines policy were accessible [27]. The key challenge for the new Africa’s National Care (ANC) led government to develop the ANC draft policy into a truly national policy, and WHO was invited to participate from the start. In 1996 the final NMP document was confirmed by the Minister of Health with the following objectives:

1. Develop a pricing plan for medicines to be used in South Africa in the public and private sectors

2. Develop a plan to ensure that medicines are tested and evaluated for effectiveness in the South African context of treatment, using epidemiological approaches

3. Develop an Essential Medicines List to be used in the public sector and prepare treatment guidelines for health personnel

4. Develop specific strategies to increase the use of generic medicines in South Africa

5. Prepare a plan for effective procurement and distribution of medicines in South Africa, particularly in the rural areas

6. Investigate traditional medicines

7. Rationalize the structure for pharmaceutical services [27; 28]

The real challenge was to reduce overconsumption in the specific parts of the system, for instance in the hospitals, while keeping facilities available for everyone. Apart from educational programs against overuse of drugs, there was a challenge to make savings and to strengthen the rural services, which were the main source of health care for the majority of the population. Key factors to reduce overuse and waste of medicines were the development of national treatment guidelines and lists of essential medicines for all levels of health care. South Africa’s NMP was supported by WHO supplying information on practical experiences from successful countries, such as Zimbabwe and Australia. However, the new medicine law, which included several progressive, but controversial pricing policy components, such as generic substitution and parallel importation, was challenged in court by the research-based local and international pharmaceutical industry. [5][15]

The United Kingdom (UK)’s – generic competition and parallel trade

The national medicine policy in the United Kingdom is provided by the National Health Service (NHS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) which have an impact on regulation, R&D and reimbursement processes. The National Health Service is the largest and the oldest single-payer healthcare system in the world (13). England, Wales and Northern Ireland have two key national HTA (Health Technology Assessment) organizations such as the NICE and the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA). NICE is an independent organisation responsible for providing national guidance for the NHS in the UK on promoting good health and preventing and treating ill health. NICE role, as an independent organization, is to produce guidance (advice) for the NHS on how to treat health conditions. Many crucial and life saving medicines are approved through NICE appraisals process. Changing R&D environment is traced by NICE to discover the value of new treatment possibilities. NHS medicines management policies are set at a local level, for example by NHS trusts and Clinical Commissioning Groups. The organizations such as NICE, NHS, the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) advice and support for delivering quality, safety and efficiency in the use of medicines[15].

Consumption of generic medicines in the UK (and Germany) contributes to the creation of the most mature markets in the world. The generic medicines have a broader aim of reducing expenditure. In the UK there are few direct drug pricing controls. The brand's price is set with the PPRS and the drug is then reimbursed by the NHS according to the manufacturer’s list price. The major medical issues such as cancer, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, kidney disease, long-term conditions, mental health, old age, and stroke care are define by National Service Frameworks (NSF), which is a policy set by the NHS. The standards of care are developed together with health professionals, patients, carers, health service managers, voluntary agencies and other experts to set clear quality requirements for care, based on the best available evidence and services that work most effectively for patients. NSF offer strategies and support to help organisations achieve above mentioned objective [6][14]. As a consequence, government spending on drugs are partially covered by patient co-payment as prescription charges. There is a monitoring system for discounting in retail and hospital pharmacies. Thanks to fully flexible management of commercial agreements, including the collection of further clinical evidence, new value of medicines can be approved more regulary [29].

However, these are not key pricing and reimbursement tools compared to the ones existing in other countries. The gratest factors having impact on price level are parallel import and a generic competition [15].

Poland – Development of medicines policy is under creation

Drug policy is an integral part of a healthcare system. Development of medicines policy, as recommended by WHO and should be carried out with the involvement of all stakeholders. Medicine’s policy covers also health education and prevention for patients. The goverement, in the process of medicines policy development should take into account the constant progress in life sciences, the improvement of treatment methods, and the economic and social situation: demographic changes – first and foremost the aging society, its varied health status, the level of citizens' wellbeing. The optimization of pharmacotherapy is critical in the right medicines policy. The goverment implements the drug policy through legal and regulatory pathway and utilizing broad-based education. The drug policy is an interdisciplinary field and many decision centers can help shape it, but the role of the Ministry of Health is the key. In Poland the initiator and main coordinator of the drug policy is the Minister of Health, equipped with statutory powers. The implementation of the drug policy is also dependent on non-governmental organizations: from manufacturers, distributors, pharmacists, consumers, to doctors, who choose treatment pathways. Because of the interests of these groups which vary and are sometimes contradictory, the agreement between them on the basic principles of the medicine policy in the context of broad public consultation should be worked out. It is important that in the process of developing the drug policy, the goverment will respond to the growing needs of patients and the ambitions of the physicians according to the rapid progress of life sciences. At the same time, the strategic problem of balancing the increase in public funds financing essential medicines and the engagement of patient's co-payment should be solved. This requires identifying the amount of public funds allocated to medicine subsidies to prevent the deterioration of public health [31].

Nowadays, registration of new pharmacotherapy options is determined by the pharmaceutical or biotech industry. Safety, quality and efficacy are key assessment criteria in granting marketing authorisation. The drug registration system should be monitored and adaptable to the changes taking place in this respect in the acquis communautaire. Poland, like many other countries, bases the medcine policy on generic products – produced after the expiry of patent protection and the expiry of the exclusivity period. The European Union laws implemented in Poland respect industrial property protection – patents and exclusivity for innovative medicines. Reimbursement expenses in 2002 amounted to PLN 5.47 billion. In 2016, the reimbursement budget was PLN 11,504 bn, and in the period from January to July 2016, National Health Found (NFZ) spent PLN 4,681bn on pharmacy reimbursement, representing 58.41% of the total drug budget planned for 2017. The drug reimbursement under drug programs cost PLN 1 493 billion, or 52.27% of the budget. Chemotherapy drugs – PLN 329 9 million, which accounts for 54.57% of the budget [17]. Apart from therapeutic benefits of drugs, safety and the cost-effectiveness of therapy are important factors. Particularly, the reimbursement lists should include medicines that enable effective treatment, reducing mortality and improving quality of life, but taking into account cost-effectiveness. The WHO's list of generic medicines should be included in the first place of reimbursement lists.

In Poland the reimbursement policy moves in the desired direction. The reimbursement analysis shows that spending on innovative molecules rises – from January to November 2016 more than 20 new molecules or combinations of molecules were included in the reimbursement scheme. Although the situation has improved in the recent years, access to innovative therapies in Poland remains one of the lowest in Europe.

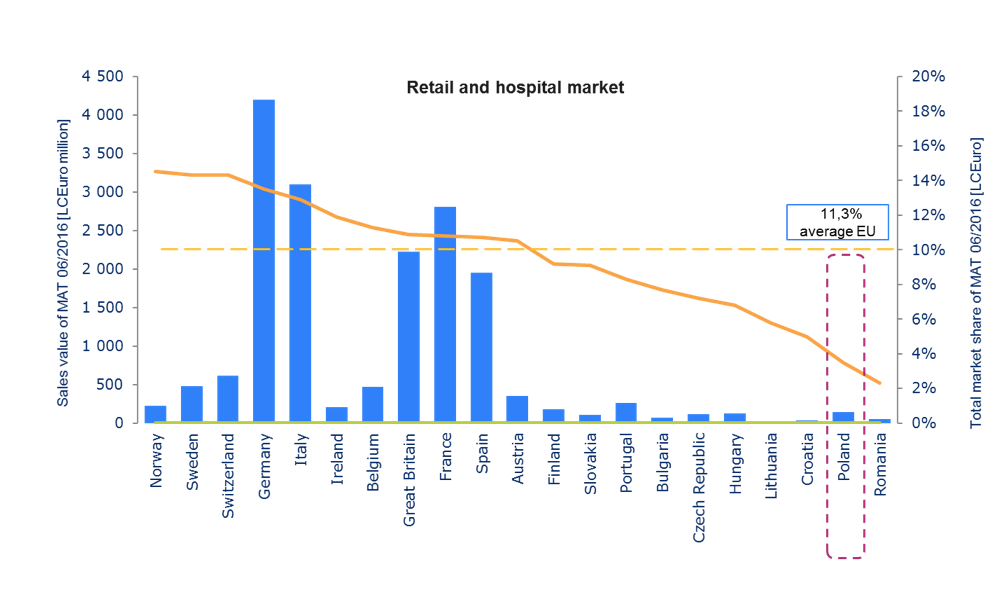

Source: IMS Midas | Retail market (ATC1: A-V, Rx) | Hospital market (ATC1: A-V, Rx)| price Ex-manufacture LCEuro

In Poland 76 out of 143 molecules (mono) have been registered by EMA in central procedure since 2009. Innovative therapies have an impact not only on the effectiveness of treatment, but also on the faster return of patients to work, which means less burden for social care and a higher tax revenue. However the medicines policy that Poland aspires to will always be complex as it must address the inherent tensions of often contradictory objectives of attaining affordable access to medicines, while maintaining a viable pharmaceutical industry, and achieving quality medicines and healthcare systems[32].

Summary

The access to innovative therapies and the use of innovative drugs play an important role in the treatment of severe, chronic and rare diseases. This includes the criteria for the selection of reimbursed drugs and the determination of the level of reimbursement, hence the need for changes in co-payment rates. The drug reimbursement should be seen in the context of epidemiology and demographic changes, and include both direct and indirect costs.

In Australia the medicines policy is addressed to by affordable access to medicines and focuses on keep achieving high treatment efficiency through appropriate use of medicines with standards of quality, safety and efficacy and, therefore, good quality of health systems. The Australian medicines policy puts a strong emphasis on the promotion of local essential medicines manufacturers. The objectives of the Sri Lankan National Medicinal Drug Policy, on the other hand, are: sustainable and equitable delivery of the good quality and safe medicines relevant to the health care needs, therefore avoiding overuse medicines by healthcare professionals and consumers.

South African NMP was created based on practical experiences from successful countries, such as Zimbabwe and Australia. South African medicines policy objectives are: efficient treatment using epidemiological approaches, particularly in the rural areas. Medicines usage should focus on pre-established treatment pathways. Reduction of overconsumption and medicines wasting across all levels of health care as well as the increased use generic medicines were key factors taken into consideration. In the United Kingdom, the consumption of generic medicines is one of the highest among mature markets in the world. The generic medicines have a broader aim of reducing expenditure. The standards of care are developed together with many stakeholders to set quality requirements for care, based on the available evidence and services that work most effectively for patients.

In Poland the development of medicine policy is under creation. Safety, quality and efficacy are key assessment criteria. In the development process, the most important is reviewing the experiences from successful countries, analysis of patients’ treatment needs, economic and social situation. In Poland the optimization of pharmacotherapy and access to innovative therapies are critical in the target medicines policy.

The international experience presented here referring to the development of medicines policy proves different viewpoints on drug spending, regulations and practice. The drug policy is interrelated with health policy and is regulated through population, economic, culture, access to medicines, and patients’ needs. NMP is the result of a complex process of development, implementation and monitoring. First, the policy development process results in the formulation of NMP. Secondly, strategies and activities that aim to achieve policy objectives are implemented by various stakeholders. Finally, the effect of these activities is monitored and the policy is adjusted if necessary. Throughout the process, careful planning, consideration of the political climate and the involvement of all stakeholders are all needed.

The drug policy as an integral part of the health policy and should be flexible, keep pace with systemic changes in health care and changing health needs of the society. Regardless of the model of health protection, the goverment is responsible for the public health.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Kanji N, Hardon A, Harnmeijer JW, Mamdani M, Walt G: Drugs Policy in Developing Countries. 1992, London: Zed Books, 136

- Another Development in Pharmaceuticals. Development Dialogue, Volume 2. 1985, Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, http://www.dhf.uu.se/publications/development-dialogue/another-development-in-pharmaceuticals/_16/08/2017

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmaceutical_policy_16/08/2017

- WHO: Equitable access to essential medicines: a framework for collective action. 2004, Geneva: World Health Organization,

- Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R: Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9659): 240-9. 10

- Dukes MNG HRFM, de Joncheere CP, Rietveld AH: Prices, affordability and cost containment. 2003, Geneva: Drugs and Money, World Health Organization; 2003, 7

- United Nations: Delivering on the Global Partnership for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals, in MDG Gap Task Force Report. 2008, New York: United Nations

- Calabrese LH: Changing patterns of morbidity and mortality in HIV disease. Cleveland Clinical Journal of Medicine. 2001, 68 (2): 109-110

- WHO: How to develop and implement a national drug policy, in WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. 2003, Geneva: World Health Organization, Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4869e/ 18/08/2017

- WHO: Guidelines for developing national drug policies. 1988, Geneva: World Health Organization, available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/1988/9241542306_eng.pdf 18/08/2017

- The Global Use of Medicines: Outlook through 2017. Report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics

- Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice20136:5. “National medicines policies – a review of the evolution and development processes”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essential_medicines_policies 14/.08/.2017

- http://www.health.gov.au/nationalmedicinespolicy 15.08.2017 Am I entitled to NHS treatment when I visit England?". www.nhs.uk. 21/08/2017 [14]

- http://www.hta.nhsweb.nhs.uk 27/08/2017

- WHO: How to develop and implement a national drug policy, in WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. 2003, Geneva: World Health Organization

- blog.dzp.pl/ rynekaptek.pl 27/08/2017

- https://www.infarma.pl/biuro-prasowe/aktualnosci-i-wydarzenia/konferencja-%E2%80%9Epulsu-medycyny%E2%80%9D-i-%E2%80%9Epulsu-farmacji%E2%80%9D-na-temat-polityki-lekowej-panstwa/ 26/07/2017

- http://www.rynekzdrowia.pl/Farmacja/Liczymy-na-kontynuacje-dialogu-dotyczacego-regulacji-w-polityce-lekowej,168800,6.html 24/08/2017

- http://www.health.gov.au 26/08/2017

- WHO: Country pharmaceutical situations; Fact Book on WHO Level 1 indicators 2007. 2009, Geneva: World Health

- WHO: The World Medicines Situation. 2004, Geneva: World Health Organization, available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s6160e/s6160e.pdf 21/08/2017

- Hamrell S, Nordberg O: A Search for Balance: Pharmaceuticals in Sri Lanka. Making National Drug Policies a Development Priority: A Strategy Paper and Six Country Stories. Development dialogue. Edited by: Weerasuriya K. 1995, The Journal of The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 1-available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js19173en/ 22/08/2017

- Vitry A: LJ, Mansfield PR Is Australia's national medicines policy failing? The case of COX-2 inhibitors. Int J Health Serv. 2007, 37 (4): 735-44. 10.2190/HS.37.4.

- Hamrell S, Nordberg O: Australian National Drug Policies: Facilitating or Fragmenting Health. Australian National Drug Policies: Facilitating or Fragmenting Health. Edited by: Murray M. 1995, The Journal of The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/es/m/abstract/Js19177en/ 23/08/2017

- Department of Health and Ageing, Quality Use Of Medicines: A Decade Of Research, Development and Service Activity 1991 – 2001. 2001, Australian Government, Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/nmp-pdf-qumresearch-cnt.htm 23/08/2017

- World Health Organization: Developments in the South African Drug Action Programme. 2001, Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js2230e/2.html#Js2230e.2.1 25/08/2017

- Department of Health: National Drug Policy for South Africa. 1996, Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js17744en/ 23/08/2017

- Walley T, Earl-Slater A, Haycox A, Bagust A: An integrated national pharmaceutical policy for the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2000, 321 (7275): 1523-6.

- http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4869e/14/08/2017

- http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_EDM_2004.4.pdf 21/08/2017

- Jahnz-Różyk K, Kawalec P, Malinowski K, Czok K: Drug Policy in Poland, Value In Health Regional Issues 13 C, 2017, 23-26.